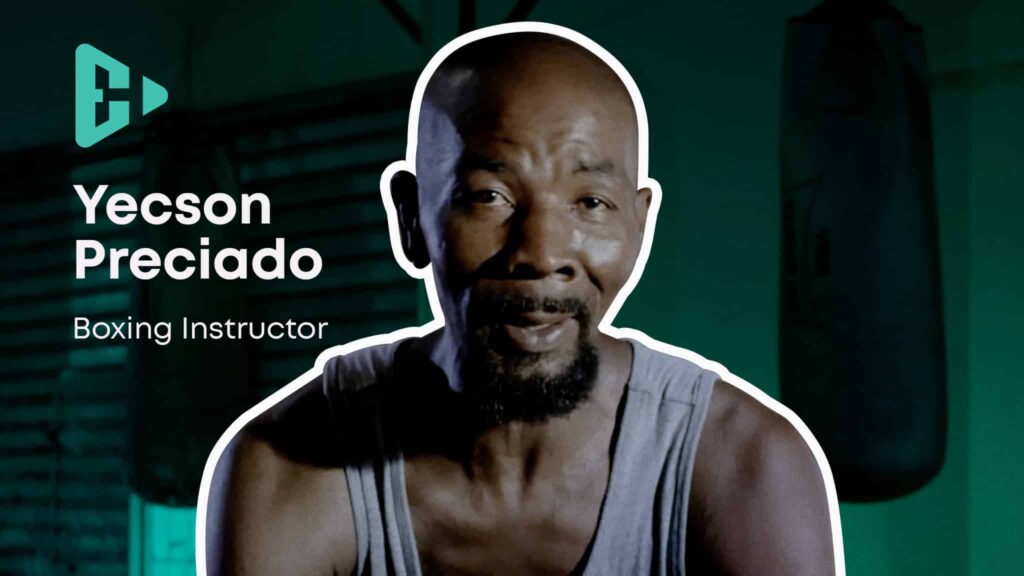

Yecson Preciado was born and raised in Guayaquil, a port city which serves as Ecuador’s commercial capital, but also has the highest poverty rate in the country. He was brought up by a dangerous father who regularly abused him as a child. At just ten-years-old, Yecson had enough and chose to run away to live on the dangerous streets, rather than be beaten by his parent.

He spent two months on his own, before he was adopted by a local family. When his new mother asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, Yecson, likely as a result of his violent past, told her his dream of becoming a professional boxer.

Yecson’s new family helped him pursue his passion by buying him all the gear he needed to get started, and set him up in boxing classes for teens. He spent the rest of his childhood spar boxing with his mentor, Chango, and went into the sport professionally.

Yecson fought some of the country’s greatest boxers and managed to become a local legend, before finally retiring. He now works as a security guard at the Guayaquil port, but can barely feed his family on his meager salary.

How Does Yecson Preciado Make A Difference?

Yecson, like many Ecuadorians, lives below the nation’s poverty line. The country’s economy has been in decline for nearly a decade, and during the pandemic, Ecuador’s poverty rate surged from 27.2% to 37.6%.

Despite his own personal struggles, Yecson put others’ needs before his own on a daily basis. In 2014, he opened a boxing gym and has dedicated his life to teach local children in his boxing classes, which can be a direct ticket to a better life in the impoverished country.

The decision to teach boxing classes for teens came after Yecson witnessed police mass-evict an entire makeshift neighborhood on Isla Trinitaria, a community so poverty-stricken that they lack access to clean drinking water and sewage systems. He decided to start a boxing gym to give children facing homeless the opportunity to play a sport that could lead to an exceptional future.

“I train them until the age of 13, then they can participate in a National Game,” he said of his boxing classes. “And I have to train them the best I can, because the bad ones don’t go there, only the best ones go. Later when they fight and become champions, only then they get a salary.”

Why Does Yecson Train Children?

He does not charge his students for the boxing classes or spar boxing sessions, nor does he make any money if they become successful, which few of them actually do. He created the gym to be a form of a community center for children facing homelessness, and to become a guiding figure to those who lack stability.

“I do this because my students become to be like my sons and daughters. I have a commitment to them, and always, the first thing that has to be the boxing school and my kids,” Yecson remarked about the boxing classes. “I don’t want to see any children go through what I lived, nor watching a kid using drugs, or to be killed a tender age. Can you picture the youth now? Kids are killed at 18 or 20 years old.”

What Is It Like On The Streets Of Yecson’s City?

In 2020, homicide rates in Ecuador surged to the second highest in all of Latin America and the Caribbean with 1,357 murders. Yecson’s hometown Guayaquil became the most crime ridden city in the country, and was ranked the 50th most violent in the world by Insight Crime.

Due to a surge in homicides and gang-related crime, Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso deployed thousands of military troops to “strengthen control” of the country, and prevent drugs and weapons from making their way onto the streets in early 2022.

Did You Miss Laurynas Buzinskas’ Feature?

Click HERE To See His Full Showcase

Ecuador is situated between the world’s largest cocaine producers, Columbia and Peru, and both favor using Guayaquil to traffic drugs to the rest of the globe. The country seized 210 tons of narcotic shipments in 2021 alone.

Lasso blamed warring Colombian and Mexican cartels for the astronomical increase in violence. Yecson just wants to keep his students from falling prey to it.

What Is Yecson’s Goal For His Students?

“[When] they realize what sports can do for them compared to the streets and drugs,” he explained about spar boxing. “I used to tell them, for example, what would you prefer? Traveling two days with headphones, then you wake up, or do you prefer to be in jail where you could get beaten. What do you prefer. They tell me the sport, then let’s do this.”

Yecson trains his students in spar boxing six days a week, from the early morning to the late afternoon. At night he works 12 hour shifts as a dock security guard from 6:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. to provide for his family and earn the money to keep his boxing gym open and teen boxing classes free.

He hopes that his boxing classes will help one of his kids reach an international elite level of competition. “My goal since I started this was to see a student of mine fighting in Las Vegas, Nevada or at the Olympic Games that is my goal,” he said. “I haven’t reached it yet. I am still here at school, moving forward. I will never stop.”

Carlos Gongora

Carlos Gongora is arguably the most famous boxer to hail from Ecuador, and came up in the boxing world in a very similar way to the child spar boxing students that Yecson trains six days a week at his gym Trinibox.

Gongora is the eighth of his single mother’s eleven children. He never met his father and the family survived on his mother’s earnings as a house cleaner. His path from Ecuadorian poverty to world renowned boxer is what Yecson dreams of for his students.

Gongora’s uncle is legendary Ecuadorian boxer Segundo Mercado, who represented the country at the 1988 Summer Olympic games in Seoul, Korea, and turned professional as a middle weight, before retiring with a 19-10-2 record in 2003, after failing to defeat WBA super-middleweight champion Frankie Lilies when the fight was stopped after five rounds.

At the young age of twelve, Gongora attempted to follow in his uncle’s footsteps by traveling to the Ecuadorian city of Coca, which was eight hours away from his hometown of Esmeraldas, to take boxing classes from the city’s reputed spar boxing trainer.

When Gongora arrived in Coca with his older brother, the gym’s head trainer sized him up and rejected him, stating that the pre-teen wasn’t built for boxing. He was turned away and told to return home, but Gongora was determined and found a boxing gym in the city of Napo to train him.

Gongora threw himself into taking boxing classes to learn how to spar box, and returned to Coca to prove to the trainer who had turned him away, that his decision was a mistake.

Instead of giving up, Gongora went to another gym, this one in Napo, to prove himself ring worthy. But he never forgot about Coca. “I came back a year later, and I beat up all the fighters that were there,” he recalled.

In 2006, the southpaw middleweight fighter made it to the amateur finals of the South American Games before losing to Venezuelan Alfonso Blanco. The next year he took home the bonze medal in the Pan American Games, but lost the 2007 World Champions to Matvey Korobov.

He represented his country at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing and again as a heavyweight at the 2012 Olympics in London. He failed to medal at either competition.

Gongora transitioned into professional boxing in 2015, where he has won 15 fights by knockout, five by decision, and has only been defeated a single time. In December 2020, the Ecuadorian boxer won the IBO super middleweight title by knockout against Ali Akhmedov at the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Hollywood, Florida.

He retained his title against Christopher Pearson when he knocked out the American on April 17, 2021, but lost his belt to Lerrone Richards by decision after a grueling 12 rounds at the AO Arena in Manchester, England in December 2021.

Donate

Yescon does not charge his students for spar boxing or boxing classes at Trinibox. He funds the gym by working 12-hour overnight shifts at the dangerous Guayaquil docks six days a week. He has no mode of transportation, and often goes without eating to keep his family fed and underprivileged students boxing.

In a country where those in poverty live on less than $5.50 a day, a small donation to Trinibox can make a life changing difference towards the futures of vulnerable child athletes and the man who has dedicated his life to teaching them.

Please donate to:

- www.trinibox.org/en (English)

- www.trinibox.org/es (Spanish)